AI is a normal technology

In a previous article, I made a distinction between AI hype and pragmatic AI. One of the most persistent hype threads is the obsession with existential risk — the idea that Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) or Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) could end civilization or make humans obsolete.

This red-herring is far removed from any reality, and distracts from real risks and challenges in building, deploying, managing, and using AI systems safely.

A recent essay, AI as Normal Technology by Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor, digs into this idea in depth. It’s a long but worthwhile read, and it frames the debate better than most “AI doom” think pieces. The authors argue that AI behaves like every other major technology we’ve invented: it moves fast in theory, but slow in practice. It introduces risks, but also has built-in limits. And it’s something we can, and should, control through normal governance, not panic.

Here’s the gist of the argument:

The Speed of Progress

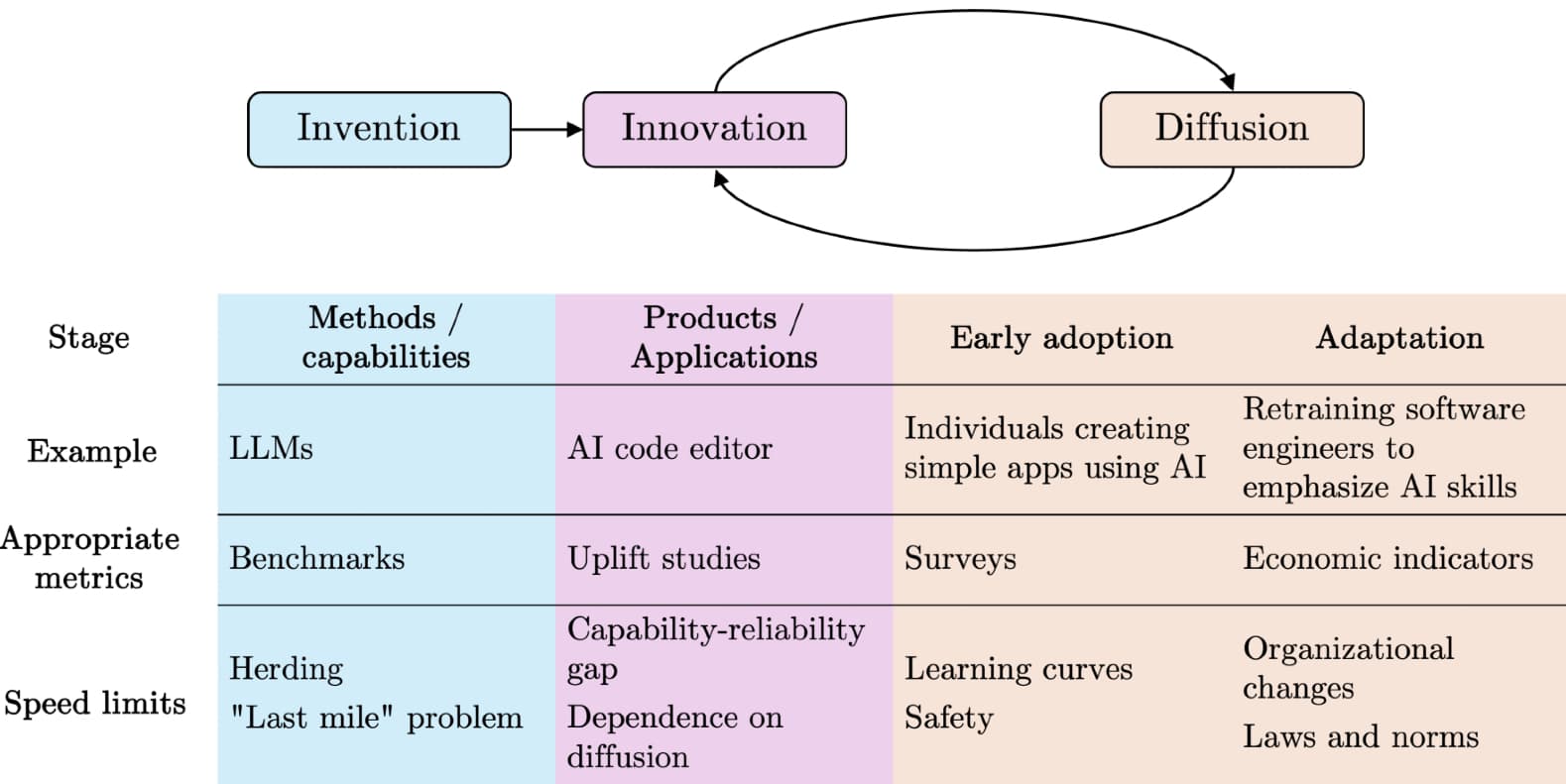

The essay splits technological progress into three phases:

- Invention: Creating and improving new AI technologies, like LLMs.

- Innovation: Applying the new technology to interesting problems in a useful way.

- Diffusion: Getting the new solutions widely adopted in the real world.

AI invention is fast. Innovation is slower. Diffusion is glacial, especially where safety, trust, or regulation matter. That’s not unique to AI: electricity and internal combustion engines followed the same pattern.

Real-world examples back this up. Generative AI may seem ubiquitous, but usage data tells another story: even among people who’ve tried it, it only accounts for a few percent of total work hours. Adoption isn’t about access; it’s about people, organizations, and institutions adapting, which always takes decades.

Benchmarks like “GPT-4 passed the bar exam” don’t tell us much: scoring high on a test is not the same as practicing law. The authors point out that benchmarks tend to measure what’s easy to test, not what’s useful. Real progress comes from real deployment, and that’s where AI (or any tech) slows down.

The Superintelligence Trap

The authors contrast two worldviews:

- Superintelligence view: Smarter AIs will inevitably surpass human control.

- Normal technology view: AI is powerful but limited, and stays within human and institutional boundaries.

The first view misses the nuance that human “intelligence” isn’t a fixed biological ceiling. We already augment ourselves through tools, organizations, and networks. AI just adds another layer. The idea of a runaway “intelligence explosion” doesn’t hold up when you unpack it.

What actually matters is power: who controls and benefits from technology. Humans have always extended their power through tools, and AI is no different. The real risks come from concentration of that power, not from AI itself gaining autonomy.

The so-called “control problem” is often framed as an engineering issue: aligning AIs with human values. But in practice, control comes from systems, not singular models. Oversight, auditing, redundancy, and accountability all work better than “alignment” hand-waving. The authors predict that more and more human jobs will shift toward controlling AI systems rather than being replaced by them, much like how factory workers became machine operators during industrialization.

Real Risks, Not Science Fiction

Narayanan and Kapoor categorize AI risks into five buckets: accidents, arms races, misuse, misalignment, and systemic risks. Most of these are familiar from other technologies.

- Accidents: Bad models or poor deployment. Market incentives and safety regulation already push against this.

- Arms races: Companies deploying unsafe systems to compete faster. This is where regulation can help, like in road or food safety.

- Misuse: Attackers using AI for fraud, phishing, or disinformation. Model-level defenses help a bit, but the real protection is downstream.

- Misalignment: Systems doing unintended things. The famous “paperclip maximizer” scenario is hypothetical at best. Misalignment issues are mostly engineering problems, not existential ones.

- Systemic risks: The real issue. Bias, inequality, disinformation, concentration of power, and erosion of trust. These are social and political problems, not technical ones, and they’ll d policy and institutional fixes, not AI safety labs.

AI will absolutely cause disruptions, but they’ll look more like the Industrial Revolution than a robot apocalypse: job shifts, inequality, policy lag, and social adaptation.

Policy and Governance

The authors call for resilience — the ability to absorb shocks and adapt — rather than “AI nonproliferation” or extreme precaution.

Restricting AI to a few actors sounds appealing but fails in practice. It’s unenforceable, consolidates power, and makes the ecosystem brittle. Instead, we should:

- Encourage distributed governance, with many independent regulators and actors.

- Fund risk and impact research, not just capability research.

- Require transparency and incident reporting from AI deployers.

- Build technical capacity in governments, not just in big tech.

- Promote AI literacy and open competition, so control doesn’t centralize.

They also warn against regulation that freezes innovation by over-generalizing (this specifically is my own worry regarding the EU AI Act). For instance, labeling all hiring or insurance uses as “high-risk” misses a lot of nuance. The key is balance: move too fast and you lose trust, but move too slow and you outsource innovation and accountability to private companies.

Don't panic

Narayanan and Kapoor’s main point is simple: it’s a powerful, evolving, and very normal technology that will follow the same messy path as every other major innovation. The danger isn’t rogue superintelligence. It’s bad deployment, weak governance, and over-centralized control.

AI will change how we work, communicate, and build, just like electricity, combustion engines, computers, and the internet did. But it’s still a tool. The right approach isn’t fear or worship, but clarity and competence. It's just another tech, anyway.